Ikebana is the Japanese art of flower arrangement that originated over six hundred years ago. While some of Japan’s most traditional strains of flower symbolism have mellowed out in modern times, ikebana is making a comeback. We’re fans of flower arranging in all forms – as long as it’s done with care – so we have to admit that if you’re looking for some Insta-worthy floral art, ikebana has got the goods.

What Is Ikebana?

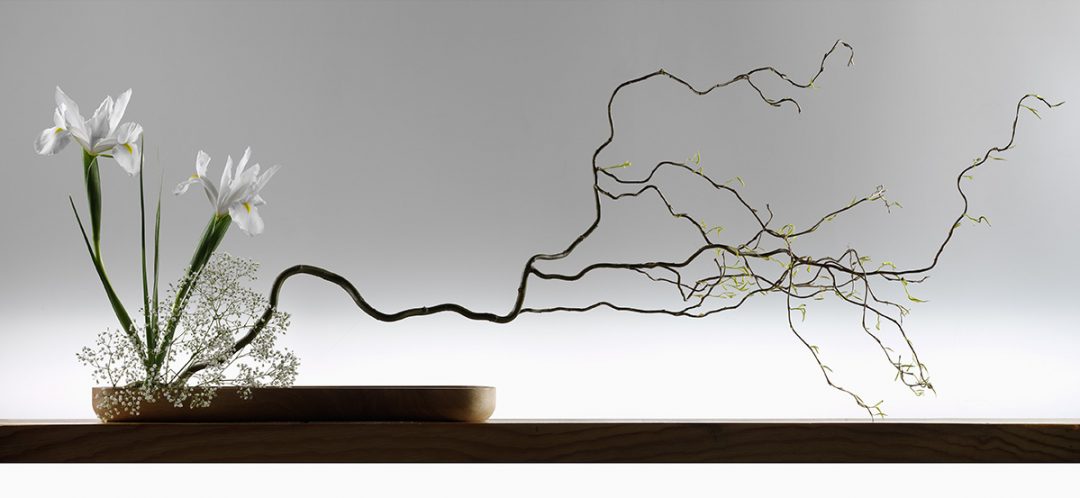

Ikebana translates literally as “flowers kept alive.” This Japanese flower arranging tradition is as much about the process as the finished product. Flower symbolism takes on another life in ikebana: it’s not just about the plants, but also everything else, including the container and even space not occupied by flowers.

Modern viewers might describe a typical ikebana arrangement as minimalist or precise, but that simplicity masks a whole universe of meaning. In fact, ikebana practitioners see it as a way to distill the beauty of the entire natural world through the elements of a refined flower arrangement.

So what exactly is an ikebana artist trying to achieve through that act of arranging flowers?

The Purpose of Ikebana

Ikebana is about reflecting harmony and balance between opposing elements – for example, between life and decay (think a withered flower and a new bloom in the same arrangement), or between extravagance and simplicity. Flowers, leaves, branches, and stems are arranged to reflect the beauty of nature and evoke emotions in the viewer.

The Common Elements of an Ikebana Arrangement

The basic elements of all ikebana arrangements are color, line, and mass. Ikebana symbolizes the beauty of all components of the natural world working in harmony. Ikebana practitioners don’t just use flowers and greenery but can add twigs, moss, stones, and even fruit.

Duality is also a prominent element of ikebana. That means typical pieces are all about the relationships, balance, and tensions between opposing forces: life and death, full and empty space, and extravagance and simplicity.

The Principles of Ikebana

- Minimalism – “Less is more” is a common theme in ikebana. The goal is to evoke strong emotions with few elements. Adding more doesn’t necessarily make an arrangement better.

- Asymmetry – Asymmetry is an important component in ikebana. Nature is never perfectly symmetrical. Arrangements that tactically use asymmetry can create interest with the clever use of negative space.

- Harmony – Yin-yang principles in design do not necessarily mean symmetry but rather the balance between the different flowers and elements in a composition.

- Wabi-sabi – Wabi-sabi refers to emotional responses to art or nature. Wabi is associated with melancholy, nostalgia, desolation, and loneliness. Wabi can invoke feelings of compassion and sadness. Sabi is associated with humility, ruggedness, durability, timelessness, and restraint.

- Ephemeral – Transitory nature of reality. Ikebana arrangements by their very nature are not meant to be permanent but last for a certain period of time. This component is powerful in evoking strong feelings.

- Spatial dimensions – The lines of the composition capture and guide the attention of the viewer. Positive and negative space can be carefully manipulated to create aesthetically pleasing elements.

- Color – Colors are carefully selected in ikebana to create a unified arrangement. Color influences perception in ikebana as it does in any visual art form. Floral displays can emphasize a single color or use contrasting colors for an element of drama.

Three Primary Stems of Ikebana

- Subject stem or Shin – the tallest stem

- Secondary stem or Soe – the second tallest

- Object or Tai or Hikae – the shortest in three stem arrangements

What Flowers to Use for Ikebana Arrangements

Subject Flowers for Ikebana

Iris, toad lily, bird of paradise, flowering plum, flowering cherry, sunflower, calla lily, flowering quince, pine branch, snake plant, gladiola, freesia, monstera

Secondary Flowers for Ikebana

Rose, carnation, dahlia, peony, hawthorn, eucalyptus, snake plant, thistle, daffodil, chrysanthemum, sword fern, larkspur

Object Flowers for Ikebana

Crysanthemum, gerbera daisy, daffodil, carnation, mustard flower, tulip, rose, sweet pea, foxtail fern

Greenery and Filler for Ikebana

Fennel, Burnet, Ruscus, rosemary, baby’s breath. snapdragon, misty blue, lace flower, solidago, asparagus, hypericum

The History of Ikebana

Ikebana first arose from floral offerings left at Buddhist temples over 600 years ago, evolving through many iterations into a secular art form. In early years, the Japanese flower arranging style known as tatehana, or “standing flowers,” dominated ikebana. It was common in religious and political spaces. It grew so formal and rigid with rules that the more simplified, free-spirited style of nageire, or “flowers thrown in,” was developed as a reaction, around the 16th century.

Famous Schools of Ikebana

The first major ikebana school was Ikenobo. Ikenobo originated around the 15th century by the Buddhist monk Senno. It was displayed in a tokonoma, an alcove in traditional Japanese homes meant to display art. Early ikebana design was based on triangular design principles.

Ikebana remained prominent enough to be simplified and adopted as a popular hobby for upper-class women in the West during the 19th century. During this time Ohara Unshin founded a new school of ikebana: The Ohara School. He developed a simplified approach which became known as the Moribana style in ikebana.

In 1927, Sōfu Teshigahara founded the Sogetsu School to further break away from traditional rules. The ongoing evolution took it completely outside the tokonoma setting. Today, Sogetsu floral displays can be found in 360-degree glass displays at prominent exhibitions, such as New Years’ celebrations.

Styles of Ikebana

Rikka

The oldest form of Ikebana derived from the Buddhist tradition. Buddhist monks refined the art of arranging flowers to embody paradise and harmony among different plants. Rikka uses 9 or 7 stem positions to guide flower placements. It also uses pine or other tree branches to complement the flowers.

- Shin – the “spiritual mountain” or highest point in the Rikka composition

- Uke – the “summit one can reach”

- Hikae or tai – called “achieving balance”, this position helps harmonize other flowers

- Sho shin – called the “waterfall” the sho shin forms the center of the arrangement

- Soe – the second tallest branch, the soe complements the shin

- Nagashi – called the “stream” this branch reinforces the representation of nature in the piece

- Mikoshi – called the “mist dividing the sacred from the common” this position defines the tension between heaven and earth.

- Do – the “body” of the arrangement, the Do uses greenery to disguise the water containers or other technical components of the arrangement

- Mae oki – the “front body” usually adds an attractive aesthetic element to complement the greenery.

Nageira

Too much structure to think about in Rikka? Try Nageirabana, or “thrown-in”. It breaks from the 9 prescribed positions and showcases flowers in their living form. Associated with Zen Buddhism, Nageirabana expresses the form of the flowering plant in a vase. This differs from Rikka which focuses more on evoking a scene in nature.

The legend of Nageira’s creation originates with the lord Toyotomi Hideyoshi, called the “Great Unifier” of Japan. Toyotomi was on a military expedition and during a temporary truce, he called for a tea ceremony. The tea master looked around the countryside and found irises growing. The tea master tossed some stems into a water container Toyotomi said, “What a clever throw-in.”

This legend exemplifies a core principle of Nageira: that any flower can be used and no container is too humble. The floral artist simply must create harmony between flower and container. Flowers were allowed to touch the rim of the flower in Nageira, something off-limits in traditional Rikka.

Seika or Shoka

Seika was a variation that evolved out of nageirabana. Seika kept several core principles and distilled them into a simple form of three parts representing heaven, earth, and man. Traditionally, they use a triangular, asymmetrical structure.

Chabana

Chabana refers to a specific variation of ikebana used for tea ceremonies. The name translates as “tea flowers”. Chabana can be considered a variation on nageirabana that uses only the flowers themselves and a vase.

Moribana

Moribana (“piled-up flowers”) was founded by the Ohara School of ikebana. It became popular in the 19th century and is what gives shape to the arrangements many people think of when (or if!) they think about ikebana. It differs from nageirabana by introducing a shallow vessel that can be viewed from 360 degrees. Moribana also uses the upright, cascading, and slanted types.

Many other schools adopted the use of Moribana. Traditional ikebana was designed to be displayed in alcoves, called tokonoma. Moribana, on the other hand, was designed to be appreciated in drawing rooms and entrance halls.

Moribana itself has a number of forms which include Hana-isho, Heika, and Hanamai. These forms themselves have variations that focus on different purposes, from harmonizing an office space to creating realistic landscapes with flowers.

Three Basic Types of Moribana

- Upright Moribana

- Water Reflecting Moribana

- Slanted Moribana

Bunjin

Bunjin variations can be found in the other styles but they deserve special mention as well. The name comes from Chinese where scholars would dedicate themselves to a life of simplicity, asceticism and the arts, including poetry and painting. The bunjin, or literati, would collect interesting stones and dwarf trees from nature. Bunjin designs are characterized by both extensive minimalism and elegance.

DIY Ikebana: Try Ikebana at Home

Today, both traditional ikebana and ikebana-inspired art showcase natural processes, thoughtful use of empty spaces, and even “flaws” in the natural world. This can be much more interesting than creating beauty through the selection of “perfect” specimens or creating artificial symmetry, remember wabi-sabi? You don’t even need to use traditional Japanese flowers, you can use native and endemic flowers near you to create your own ikebana.

If you’re anything like us, you’re all about the DIY spirit. So if you’re itching to crank up the ikebana in your next flower arrangement, we’re rooting for you! Here’s what you’ll need to consider:

- The style: Will you go traditional with a formal “standing” style, or ride the trend of bending the rules for creativity with a loose Moribana style? Check out some examples below and think about how your flowers will look from different angles.

- The materials: Channel your inner Moribana spirit and don’t limit yourself to flowers and greenery. Throw in some rocks or moss too! As for your chosen flowers, take inspiration from flower symbolism to match a theme, or just go with the flow of what you find most aesthetically appealing.

- The container: In keeping with the ikebana tradition of creating harmony in a space, you’ll want to deliberately choose a container that works aesthetically or spatially with your chosen materials. You can select a shallow vessel in the Moribana style, a vase in traditional Rikka fashion, or use a basket. It’s up to you. Get creative!

Ikebana DIY Guidelines

- The arrangement should represent living plants

- Suggest a season with the colors and plants selected

- Keep flowers connected at the bases as if growing from the same source

- Do not cross branches or leaves

- A blossom grows from the stem and source, they should not be disassociated

- Use an odd number of stems, not even

Basic Ikebana Techniques

These are the common techniques you’ll need to know when you practice ikebana.

Cutting

Depends on how you are arranging. If you are using a kenzan to hold your flowers in place, use a straight horizontal cut. However, if you are using a vase then make a diagonal cut at 45%. The diagonal cut maximizes the surface area for the stem to absorb water, which maximizes the life of your blooms.

Trimming

Sometimes you’ll need to trim stems down to make them fit the height you want. Trimming is also essential to create clean lines that define ikebana arrangements. If you trim any small branches or twigs, your floral stems will shine. You should also trim away any leaves that would sit below the waterline.

Kenzan

The kenzan or flower frog is an essential tool for many types of ikebana designs. It holds the stems in place allowing you to place stems at different positions to create drama with angles and lines. Sometimes a second kenzan is used to enhance stability.

Stem-in-Stem

Sometimes, your vision might require thinking outside the kenzan. The stem-in-stem technique involves inserting a thinner stem into a thicker stem. This lets you create more complex angles and compositions.

Crushing Stems

Counter-intuitively, crushing the steps can prolong the life of your flowers by dramatically increasing the surface area to absorb water. This technique can also assist in creating compositions with numerous types of flowers such as Rikka arrangements.

Stem Bending

Sometimes you might want to create a shape that deviates from the lines of the stems you have. Don’t fear, many flowers have strong but bendable stems that you can turn into the shape you want. You can also make a small cut in the branch to increase the bendability of particular branches.

Protip: Suggest a Season

A goal of more advanced ikebana is to suggest a season in the arrangement itself. How can flowers suggest a season? We can offer some tips. Keep in mind the principle that all the stems spring from the same base, called the midzu-giwa.

Spring

For March and February, the winds are usually high. Consider arranging your flowers in a way that suggests windswept movement. Create a short base where the stems all come together (midzu-giwa) and let it spread wide to represent the blooming of spring flower fields. You can also bend stems into positions to invoke the effect of wind on trees and plants.

Summer

An abundance of young, green leaves symbolizes the summer. Wide and shallow vessels are popular for summer arrangements. The midzu-giwa is the shortest in summer compositions.

Autumn

Mixing in some golden or yellow leaves and blooms suggests harvest season and the changing of colors of fall. The midzu-giwa should be longer in the fall to suggest the falling leaves of deciduous trees.

Winter

The time when most trees are barren and many flower-producing plants are dormant. You can evoke the feeling of winter with the longest midzu-giwa. Do not bring the flowers representing humanity and the earth to the front. Allow for a more sparse, elongated arrangement.

FAQ

What are the rules of ikebana?

Rikka has the most formal style with classic positions for placement. View the chart above to see the traditional positions. Other styles have looser rules but generally, all maintain the 3 principles of representing nature through heaven, earth, and man with 3 primary flowers.

Is ikebana restricted to flowers?

Yes, ikebana is an art of flower arrangement. It differs from other miniature tree and landscape arts, such as bonsai and penjing, with its focus on cut flowers but shares many of the same aesthetic principles such as minimalism, asymmetry, use of lines, and contemplation of nature.

How many ikebana schools are there?

There are thousands of individual ikebana schools but the three primary schools that evolved are the Ikenobo, Ohara, and Sogetsu schools.

Our Bouqs are all about arranging flowers with care no matter what style you choose! We can’t deny the appeal of a flower arranging tradition that’s all about working with, not against, nature. In fact, we strive for just that with our seasonal, sustainable, farm-to-table Bouqs. See for yourself!

References and Sources

https://www.ohararyu.or.jp/english/styles.html

https://www.sogetsu.or.jp/e/about/creation

https://en.m.wikisource.org/wiki/Japanese_flower_arrangement

Dahlia Moonfire: photo by Dominicus Johannes Bergsma and published under Creative Commons Attribution license

Peony: photo by Agnes Monkelbaan and published under Creative Commons Attribution license

Hawthorn: photo by Eugene Zelenko and published under Creative Commons Attribution license

Chrysanthemum: photo by Reinhold Möller and published under Creative Commons Attribution license

Daffodil: photo in the public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Carnation: photo by Selena von Eichendorf and published under Creative Commons Attribution license

Gerbera Daisy: photo by Prabhupuducherry and published under Creative Commons Attribution license

Mustard Flower: photo by Nafiur Rahman and published under Creative Commons Attribution license

Fennel: photo by Rhododendrites and published under Creative Commons Attribution license

Ruscus: photo by KENPEI and published under Creative Commons Attribution license

Baby’s Breath: photo by Audrey from Central Pennsylvania and published under Creative Commons Attribution license

Burnet: photo by Phyzome and published under GNU Free Documentation License

Rosemary: photo by Prahlad Balaji and published under Creative Commons Attribution license

Snapdragon: photo by Sabina Bajracharya and published under Creative Commons Attribution license

Upright and Slanted Moribana photos by Sorin Mazilu and published under Creative Commons Attribution license

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en